By Angela Gartner

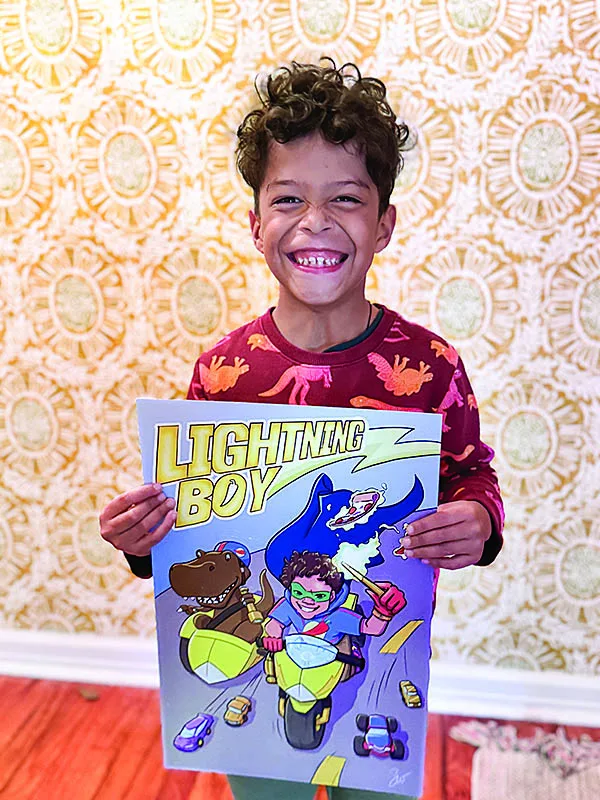

Nikki Montgomery, strategy and communications director for Family Voices National, says that her son Richie, 12, has had an alter ego since age 6. “Electric Force” is a superhero who has a magic hammer that shoots out smiley face stickers to make people happy.

The alter ego for Richie — who has RYR-1 congenital fiber-type disproportion myopathy, a rare genetic condition that impacts the muscles — was created courtesy of The Superhero Project. It provides opportunities for children and teens with disabilities or those children who are critically ill to see themselves in a way beyond their diagnosis and find their inner superhero.

“It allows families to focus on the positives and strengths in their child,” Nikki Montgomery says, adding that the drawing gets to highlight the reason Richie is special and her son gets to see his own strengths.

The project, created by Founder and Executive Director Lisa Kollins, started as a one-time camp program in 2016 and now has served more than 1,600 kids. While most kids are in Ohio, Kollins says they’ve served 47 U.S. states, including Puerto Rico and Guam, eight Canadian provinces and 25 countries total.

None of the superheroes are alike. Each child and family is interviewed individually so The Superhero Project can get to know their personality and what the child wants in their alter ego.

“I have met families at their homes, at libraries, and at coffee shops, and conducted virtual interviews, where we go through a series of questions,” Kollins says. “The first half is focused on the whole child. We work with families no matter a child’s ability. So if they are nonverbal, use a communication device or sign language, we do our best to be inclusive of everyone. We’ve even used translators several times. The second half (of the interview) is when we find out how they want to help the world.”

After the interview is over, the task of designing a poster is done through

various volunteer artists.

“All of that information, along with photos of the kids, is sent to a member of our League of Extraordinary Artists, which is what we call our global team of volunteers,” Kollins says. “So far we’ve worked with somewhere between 650 and 700 artists from six continents, a bunch of countries. We’re only missing Antarctica. So, if you happen to know someone in Antarctica.”

She says posters are donated by four printing companies and the families receive a short character story based on the child’s ideas, along with a note and bio from the artist. The project is free for all families. It has also created memorial posters for children who have passed away.

“The meaning and the impact of participating in The Superhero Project that parents share with us is amazing,” Kollins says. “When (the children) see themselves depicted so beautifully and powerfully, and they see the stuff that they love included by the artist, it really makes a difference.”

She adds that parents use this as a tool for self-

confidence, too.

“Parents also say that their superheroes foster resilience, because it becomes a practical tool that they can use when their child’s facing a challenge,” she says. “They can say, ‘Now, what would your superhero do in this moment?’ or ‘Which of your superpowers are you going to call on to make it through this test or this challenge or past this obstacle?’”

The project also has made an impact on Kollins’ life since creating it. She now is working full-time at the nonprofit.

“It’s the most meaningful work I have ever done, both personally and professionally,” she says. “These families invite me into their lives for a short time to walk along for what is sometimes the most difficult part of their journeys. And I don’t take that trust lightly.”

superheroprojectkids.org